The cobbling together of US immigration policy

Hart-Cellar might be a little over-rated?

Understanding how the U.S. immigration system came to be is essential to building a better one. Over the next year, I’ll be sharing a series of posts as I learn in public—digging into how the system works today and the paths forward to improve it.1.

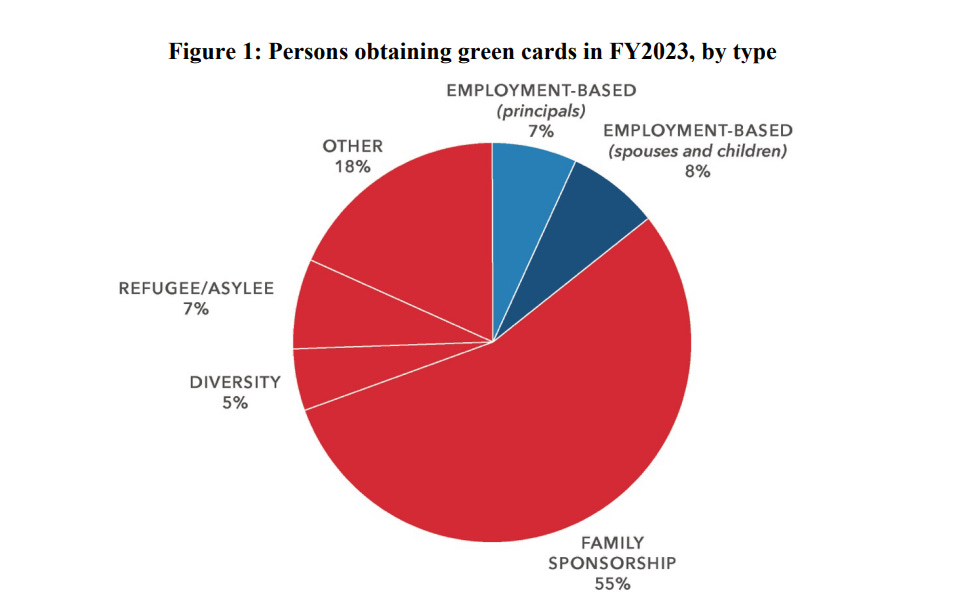

High-skilled immigration is one of the most powerful levers the US has to drive technological innovation, economic growth, and global competitiveness, but our current immigration system doesn’t prioritize it.

Jeremy Neufeld has a very helpful chart that clearly illustrates this point. Only ~7% of green cards are allocated on the basis of employment.

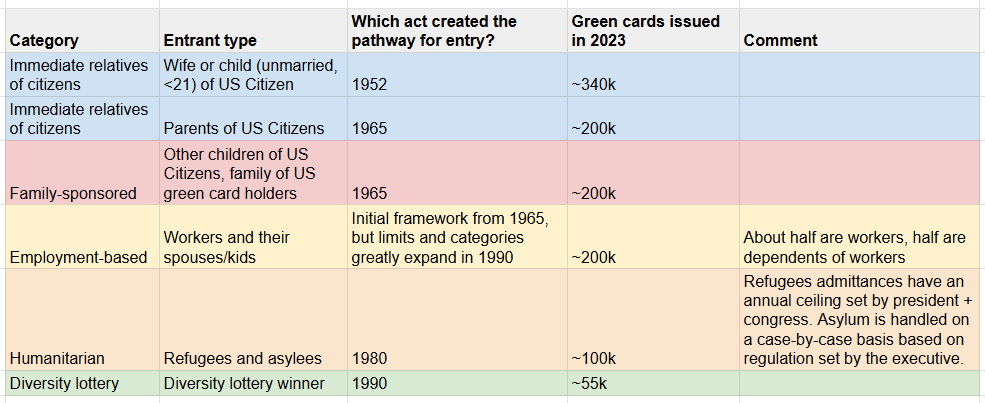

I wanted to double-click Jeremy’s data and see which laws enable which categories of green cards, to get my head around what legislation actually drives our high-skilled immigration.

Our immigration system has been kludged together by laws passed over the past three-quarters of a century. Here are the key ones:

1952: The Immigration and Nationality Act had strict quotas and allowed very little immigration from most of the world, but spouses and children of US citizens could get green cards and were exempt from quotas.

1965: The Hart-Cellar Act amended the 1952 act to get rid of national origin quotas, and dramatically increased immigration from non-European countries.

1980: The Refugee Act currently governs US refugee policy.

1990: The Immigration Act of 1990 significantly expanded employment immigration, and added a diversity visa.

2000: Trafficking Victims Protection Actcreated slots for victims of human trafficking and victims of certain serious crimes who assist law enforcement.

Here’s my best shot at a visualization about the effect of each of these laws on immigration in 20232.

To put this another way, depending on how you get your green card, here is the rule of law you are subject to3:

The biggest takeaway for me here: The oft-discussed Hart-Cellar act from 1965 is the foundation for family-based migration, but actually didn’t do too much for employment-based migration.

The U.S. has a long history of welcoming immigrants in general—but only a short history of systematically enabling highly skilled ones.

The great migration waves of the 1800s and early 1900s weren’t bringing the world’s best engineers or scientists—engineering barely existed as a field. The typical immigrant was a German farmer heading west or an Italian laborer bound for a city factory.

From 1965-1990 onwards, immigration policy focused on family reunification, not on attracting people with the most skills.

Only since 1990 have we had an immigration system that (to some extent) rewards highly-skilled workers. The change in 1990 was in the right direction. But 1990 is a long time ago now, and we can do a lot better.

Ultimately, a better high-skill immigration system will make the American people better off. This will require a change in legislation. As intractable as the legislative status quo might seem right now, it will not last forever.

At some point change will come, and it’s up to us who care to work to ensure the change is for the better. This work starts in understanding where we are, and where we’ve come from.

Two great sources that informed a lot of this post are the books:

Dividing Lines by Daniel Tichenor, which covers the entire scope of US immigration history from the start of the union until ~2000.

The Politics of Immigration by Tim Wong, in particular chapter 2 which details the existing immigration system.

Ultimately what I am trying to answer here is the question: “For someone who enters the US today under current immigration law, which actual law is governing their entry?” This is different from the question “Under previous immigration law, how many people could enter the country?”

These numbers can make your head hurt. For example, employment visas, overall the limit is 140k, but rollovers of un-used visas from family-based preference class often make this higher.

Why are there so many rollovers? It seems weird that there should be so many visas rolling over from previous years. My mental model: There are a bunch of queues for family-based preference classes that are processing people at embassies around the world. A processing backlog at one embassy in, say, Bhutan can mean that there is an extra green card slot that can be picked up by someone processing an employment-based green card who is in the US.

Having the administration of the immigration system distributed around the world means that visas get re-allocated to the centers that are more efficient at processing all the visas in their dockets. In the current system this particular feature happens to benefit employment-based visas